Burma Army expansion, abuses along Kokang-China border creating scores of “ghost villages”

Burma Army expansion and ongoing abuses since last year in mountainous areas along the Kokang-China border is making it impossible for tens of thousands of Kokang refugees to return home, according to interviews carried out by SHRF in March 2016.

Heavy fighting between Kokang and Burmese government troops was the main reason why an estimated 100,000 refugees initially fled to China in February 2015. Now continuing persecution by Burmese troops camped near their villages is preventing many of these refugees from returning home.

Still traumatized by killings and disappearance of fellow villagers at the height of the conflict last year, refugees described how Burmese troops were continuing to commit abuses against civilians, including arbitrary arrest and torture, sexual violence, looting of property, and forced labour. The Burmese troops have also laid landmines along border paths, injuring refugees trying to return home.

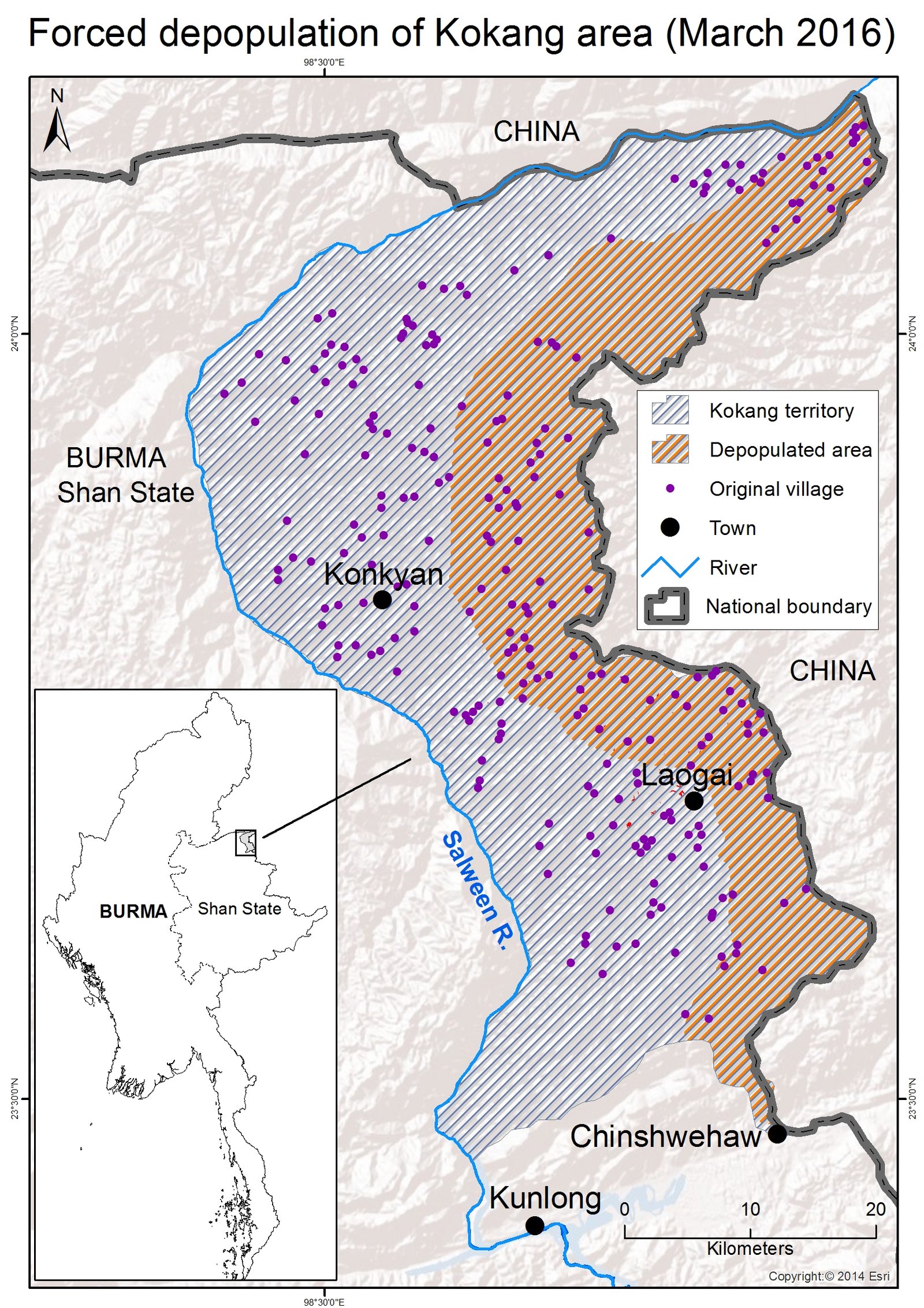

SHRF spoke to refugees from over 20 villages (in northern Laogai and Konkyan townships), who said their villages were either completely deserted or with only a few inhabitants temporarily staying to look after their farms. They said conditions were similar south of Laogai, indicating a deliberate strategy by the Burma Army to depopulate the eastern border regions of the entire Kokang self administered zone.

Stuck in China, but with no access to official refugee camps, which were closed down by the Chinese authorities last year, over 20,000 refugees are sheltering in makeshift camps just inside the Chinese border, surviving on donations from volunteers and wage labour in nearby farms. Many more have scattered to find work elsewhere in China.

SHRF is concerned that the ongoing Burma Army persecution of Kokang civilians and resulting refugee crisis are being ignored, both inside Burma and internationally. A UNOCHA update issued in January 2016 downplays the severity of the crisis, giving a figure of only 4,000 Kokang refugees left in China.

SHRF urges donors and aid agencies to seek ways to address the urgent humanitarian and protection needs of the refugees sheltering along the Kokang-China border.

SHRF also urges the new NLD-led government in Burma to seek a political, not military, solution to the conflict in the Kokang region, and to begin a new, fully inclusive peace process that does not exclude the Kokang.

1.Interview with refugee from Xiao Bang Tang village (who was tortured by Burma Army)

Male farmer, aged 49

Originally there were 151 houses in our village, but now no one dares stay there. There are only 11 families from our village staying at this refugee camp. There are about 40 people here. We survive by working in nearby sugar cane fields (in China).

There is a Burma Army camp near our village. It’s on the hill above the village. The soldiers are from IB 33. The camp was set up about 4 months ago.

Most of our village fled to China after fighting broke out last year (in February 2015), but some of the men used to cross back and tend their fields as our village is quite close to the border. On December 27 last year I went back with four other villagers.

We crossed over at about 4 pm, and went back to our village. I spent the night in my house. The next day in the afternoon, a group of 60 Burmese soldiers came to my house. They showed me some bullet casings which they said they’d found near my house. They arrested me, and also two of the other men who had returned to the village the day before.

They tied up my hands with rope and blindfolded me. Then they put me a vehicle and drove me to an army camp at Ta Shui Tang village.

They kept me locked in a room by myself. I was put in leg irons. Every day a couple of soldiers came and asked me: Did you meet Kokang soldiers? Are you a member? Where are the soldiers? Each time I said I knew nothing. Each time, they hit me, sometimes with their fist, and sometimes with a rifle butt. Some days I passed out, and blood poured from my nose.

I was kept there for 2 weeks. Finally I was released, at a village called Ywe Ba. I then walked back to the border. I was so weak, it took me about 3 hours.

The other two men arrested were released a few days after me. They had been interrogated and beaten like me, but they had also been cut with knives, on their head and on their bodies.

A week after we had been released, another man from our village, called Lo Fa Jiu (age 39) was also arrested by the Burmese soldiers. He was arrested when he had gone back to look after his fields. He was taken away for 10 days. When he came back to the Chinese side of the border, he was bruised all over his face, and had become mentally disturbed. He stayed only 3 days then disappeared.

We are staying close to the border because we want to be near our village. We want to go back and tend our fields. We used to get our main income from growing sugar cane. Each family could earn at least 5,000 yuan (approx 760 USD) a year from selling sugar cane. Some even as much as 20,000 yuan (approx 3,000 USD). Now it has been two years that we haven’t been able to harvest sugar cane. We have sold off our remaining cattle to survive here in China. Now we have nothing left.

2.Interview with villager from Hong Shi Hto village (describing burning of IDP settlement, killings, forced labour, looting by Burma Army)

Male farmer, aged 58

There were over 40 families in Hong Shi Hto village. Now most are staying in this refugee camp. We have been here since October 2015. Before that we stayed at an IDP camp called Cha He Ba, just inside the Burmese border. There were several hundred of us staying there. On October 17, a group of about 30 Burmese soldiers came and ordered us to move out. They fired their guns in the air to scare us. We pleaded with them not to force us to move. Finally, they gave us three days to move. After that, they burned down our huts. We moved to this site here in China.

We first fled from our village back in February 2015. In March 2015, three villagers from Hong Shi Htowent back to see their farms. They were caught by Burmese soldiers. Two men were slashed to death with machetes – Yi Lao Bao and Lo CaiJu. They were in their 50s. Another man, Yi Lao Er, in his 30s, was also slashed, but didn’t die. He managed to escape back to the border.

In September 2015, another villager, Yang Jing Da, in his 50s, went back to tend his cattle, and was shot at by Burmese soldiers. He wasn’t hit, but the bullets landed near his feet, and the shock deranged him. He abandoned his cattle and ran back to the border. He’s here in the camp. He’s completely lost his mind.

There are now three Burma Army camps set up around our village (Hong Shi Hto). There are about 150 soldiers staying there. There’s hardly anyone staying in the village any more. Only a few men sometimes try and go back and farm.

If anyone is staying in villages, the Burmese soldiers call them for forced labour. Only last month they did this in our village. They ordered each person to bring one piece of bamboo to their camp. Then they made the villagers clean up around their camp and fix the road. They also forced the villagers to carry goods they had looted to their camp. They were made to carry goods and building materials from dismantled houses in Ywe Pa village. There’s no one in Ywe Pa village now. There used to be over 80 households, but now it’s completely deserted. The Burmese soldiers have taken everything.

It’s the same in our village. The soldiers took everything – all our food, possessions, machinery, animals. They even took my bed.

3.Refugee from Shung Diao Ai (describing refugee injury from Burma Army land mine, disappearance of villagers)

Male farmer, aged 61

We first moved to this camp a year ago. At that time there were over 700 people staying here. In April 2015, when there was very heavy fighting near here (at Nan Tien Men mountain), shells fell near the camp, so we all had to move. We came back about three months later, but there are not many people left in this camp now – only 13 families. It’s mainly old people, children and disabled. Anyone who can afford it has moved out elsewhere. We can’t afford to live anywhere else, and we want to stay here near our old village. It’s only an hour’s walk from here.

No one can go back to our village now. The Burma Army has blocked the road to our village. They have also laid land mines at the border to prevent people crossing over.Last December, a 15 year old refugee boy was crossing over to tend cattle, when he stepped on a land mine at the border. It was only 10 minutes from here. His friend ran back to this camp, and I went with 4 other people to go and help him. He was taken to Nansan hospital, and his leg was amputated. He was originally from Hong Shi Hto village, but had been staying in Lao Huay village in China.

I haven’t been back to my village for a year. I don’t dare go back since people who were staying there disappeared last March. There was an old woman in her nineties, and her grandson, Wang Lao Liu, who was in his 20s. They were staying to look after their house, but they disappeared. No one knows what has happened to them, but we think they must have been killed. Also in March last year, three men who went back to Shung Diao Ai also disappeared. One was called Ju Ping An (in his 30s), Chi Lao San (in his 60s) and Wang Ma Liu (aged 25). They went back to check on their houses, but never came back.

I have no idea if my house is still there, or if there is anything left in it. There’s an army camp nearby and no one dares go back.

Many Kokang refugees are elderly and childrenOur biggest problem here is food. We used to get donations of rice, but we haven’t had any for 2 months. We have to try and find work to support ourselves, but it is mostly children and elderly in the camp, so they can’t work. We go and find vegetables in the surrounding hills to eat.

4.Refugees from Wa Zi Cai (sexual violence, failure to grant full citizenship cards to Kokang citizens)

Female farmer, 40s

There used to be over 60 houses in our village, but now only a few people are left in the village. Just men. Women don’t dare stay there, since some women who went back were raped last year.

Two refugee women from my village (Wa Zi Cai)were raped in May of last year. One was in her 40s – she had fled from the village, but had secretly gone back to her house. She had gone back with her husband, but he had gone to their fields, while she went alone to their house. The Burmese soldiers camped above the village saw her, and a group of 4-5 soldiers came down and raped her. 10 days later, the same happened to another woman, in her 50s. She had left her children in China to come back and take care of her house. The soldiers saw her and came down and raped her in her house.

Another woman, in her 40s, from a nearby village, Lao Ren Cai, was also raped, in August of last year. She was sheltering in China, but had gone back to check on her house, leaving her husband and children at the border. A group of Burmese soldiers came to her house and raped her. She went crying to the headman and told him what had happened.

Male farmer, 73

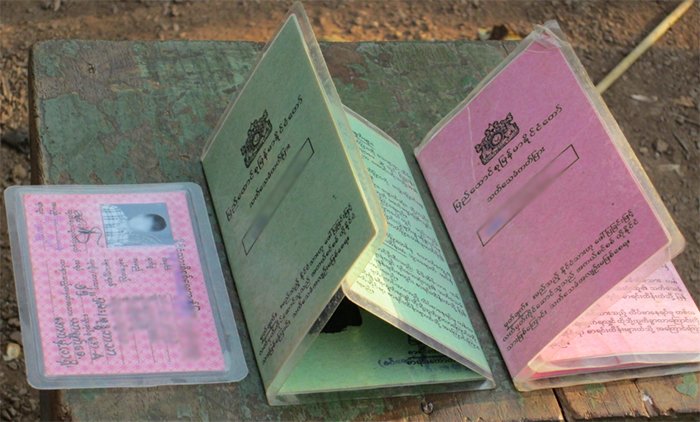

I don’t have a proper Burmese ID card. I just have a green “three-folding” document. It was issued to me in May 2009. Actually, my parents had proper Burmese ID cards, so I should have been given one too, but the authorities aren’t granting proper ID cards to Kokang people. We are not treated equally. This is one of the reasons for the war now.

Note: Green “three-folding” cards are issued to men, and pink “three-folding” cards to women. The cards state that the holders have no guarantee of citizenship. Restrictions and penalties for violation are printed on the cards. Card holders must report to authorities if they travel for more than one month. Violators are liable to two years’ imprisonment.

PDF files:

Contact person:

Sai Hor Hseng +66 (0) 62- 941-9600 (English, Shan)

Lawnt Noom Jaeng +66 (0) 63- 838-9029 (English, Burmese)