TRAPPED IN HELL

Trafficking, enslavement and torture of youth by Chinese criminal gangs in northeast Shan State since the 2021 coup

Download report: English Chinese Thai Burmese Shan

SUMMARY

This report is based on interviews with three young women and two young men who suffered severe abuse at the hands of Chinese criminal gangs operating on-line scamming, gambling and pornography businesses in the Kokang and Wa regions of northeastern Shan State of Burma.

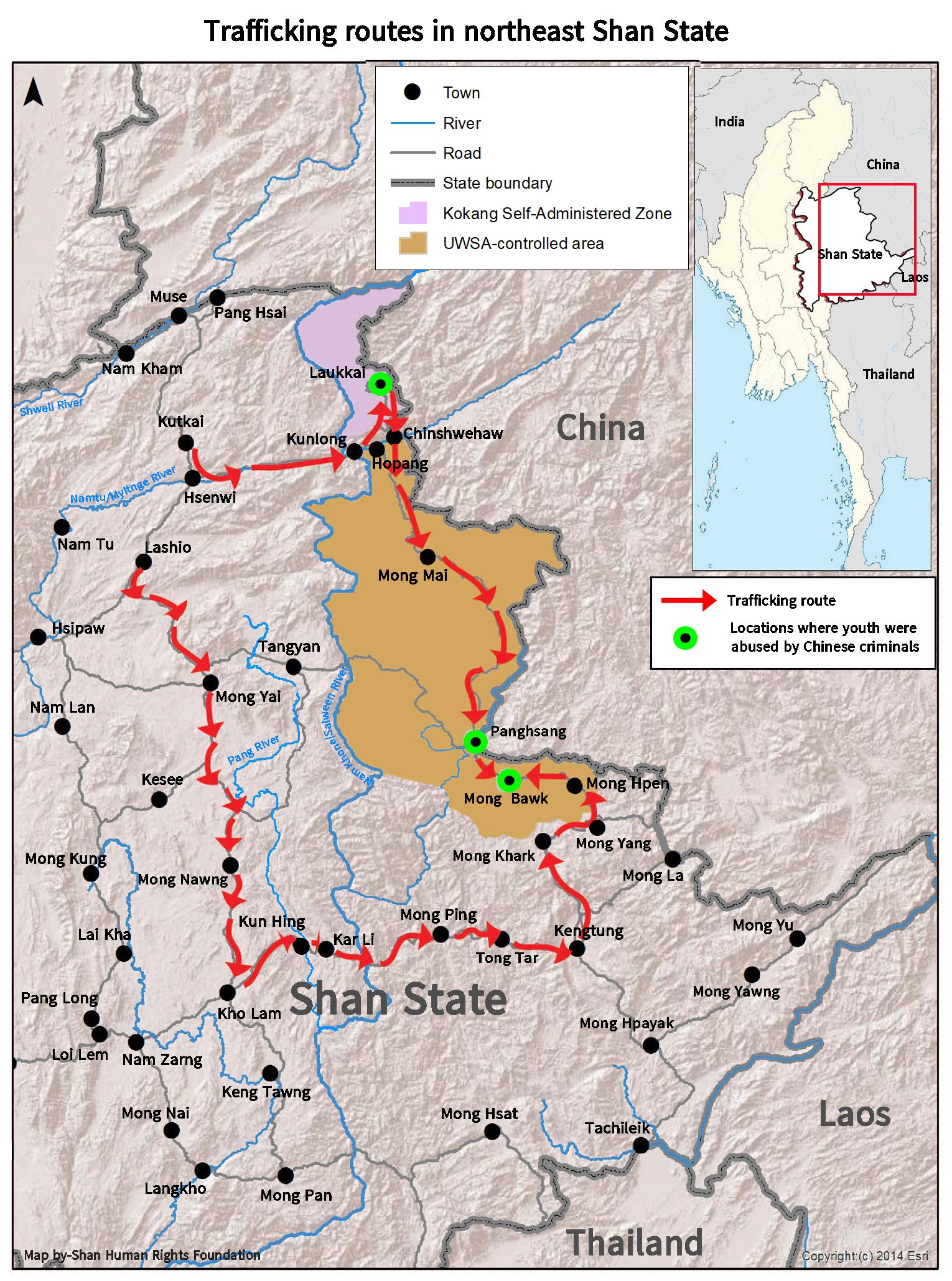

Their experiences took place after the February 2021 military coup, and in the case of four interviewees, directly resulted from their education and jobs being cut short by the coup. Three former students and one CDM nurse needed to look for work and ended up being trafficked into situations of enslavement in the United Wa State Army (UWSA)-controlled towns of Panghsang and Mong Bawk, where they were forced to scam people on-line, provide sexual services to Chinese gang members, and take part in online porn videos. When they resisted, they were subjected to physical torture and, in the case of the women, sexual assault.

The interviewee who was not trafficked, but voluntarily worked for an on-line casino in the Kokang capital Laukkai, recounted how her younger sister, who worked with her, committed suicide by jumping from a high-storey building after being accused of embezzlement and then gang-raped by her Chinese employer and his associates when unable to repay the missing funds.

Payment of up to 30,000 yuan was demanded from the trafficked victims in exchange for release. One was released after her family paid the fee. Two were released after another victim’s family used connections with the Wa authorities. One managed to escape while being moved to another location. None of the abusers has been brought to justice.

The testimonies provide clear evidence of collusion between the Chinese criminals and the local authorities. In two cases, when victims’ families contacted the UWSA liaison office in Lashio for help, the criminals were tipped off and either escaped or moved the victims to another location before being “raided”. The on-line scamming centre in Laukkai was openly guarded by uniformed members of the regime-aligned Kokang Militia Force.

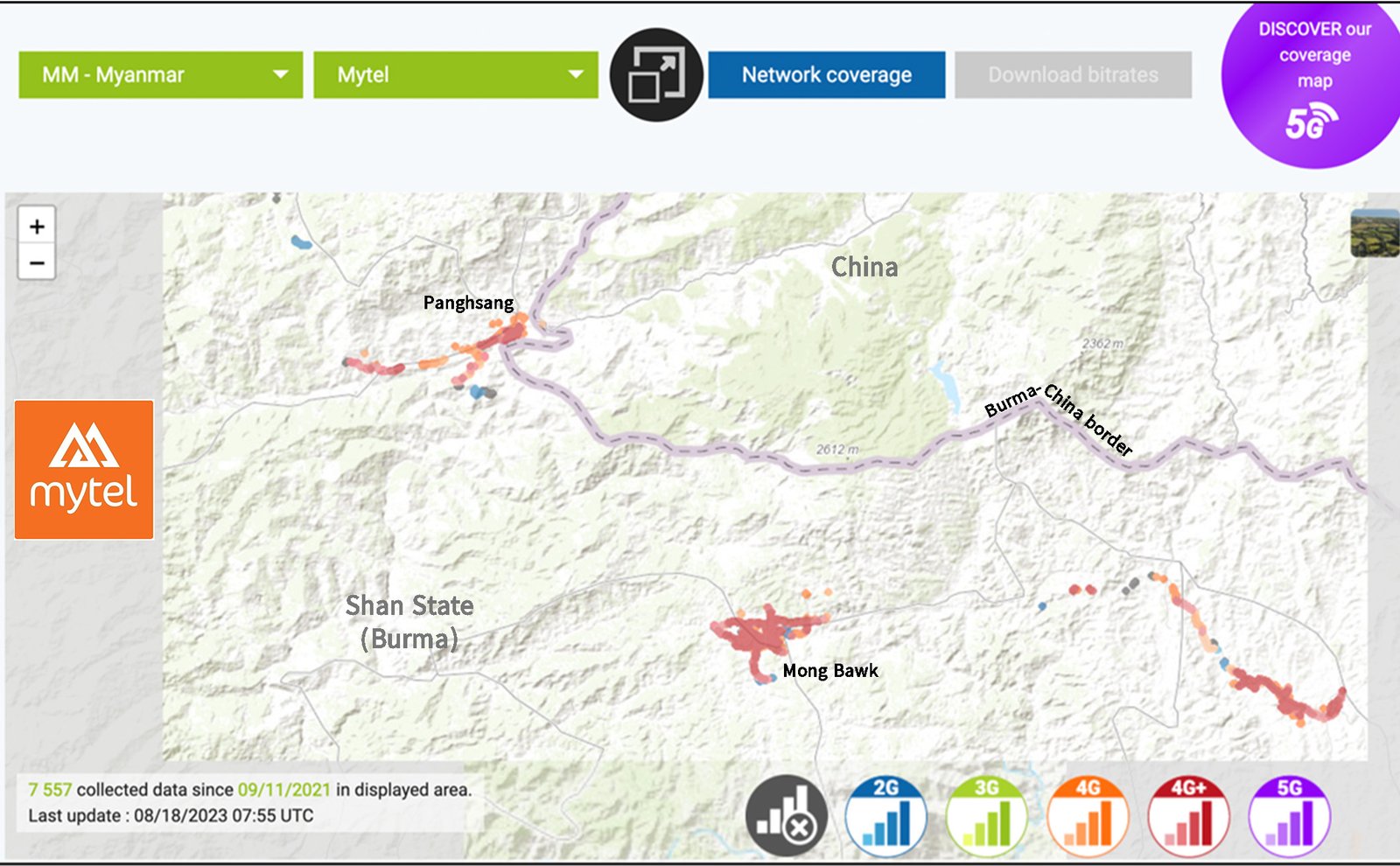

The victims forced into cyber scamming in Mong Bawk revealed that they used the Burmese military-owned Mytel network, the only Burmese telecom service in the northern Wa area — raising questions as to why the State Administration Council (SAC) regime, with its extensive surveillance capability, is failing to crack down on cyber crime on its own network.

SHRF urges the Kokang and Wa authorities to stop colluding with and protecting the criminal gangs operating in their areas, and urges China to take more effective measures to hold their citizens to account for involvement in these operations.

SHRF also urges Vietnam, whose state-owned Viettel is a joint partner in Mytel, to investigate the use of the Mytel network for cyber crime in northeast Shan State.

DESTINATIONS FOR TRAFFICKING AND ABUSE

The UWSA-controlled region of northeast Shan State

The four trafficking victims interviewed for this report ended up in the hands of Chinese criminal gangs operating in the towns of Panghsang and Mong Bawk in the region of northeast Shan State under the control of the United Wa State Army (UWSA), which has had a ceasefire agreement with the Burma Army since 1989. This region is autonomously governed by the UWSA, and has its own police force and judiciary.

Panghsang (or Pang Kham) is the UWSA capital, which lies directly on the Chinese border. Formerly the jungle headquarters of the Communist Party of Burma, the town developed rapidly in the 1990s, with the UWSA permitted by the military regime to freely expand its economic interests. This included the setting up of casinos, which formerly catered to Chinese gamblers in person, but in recent years have increasingly switched to on-line operations.

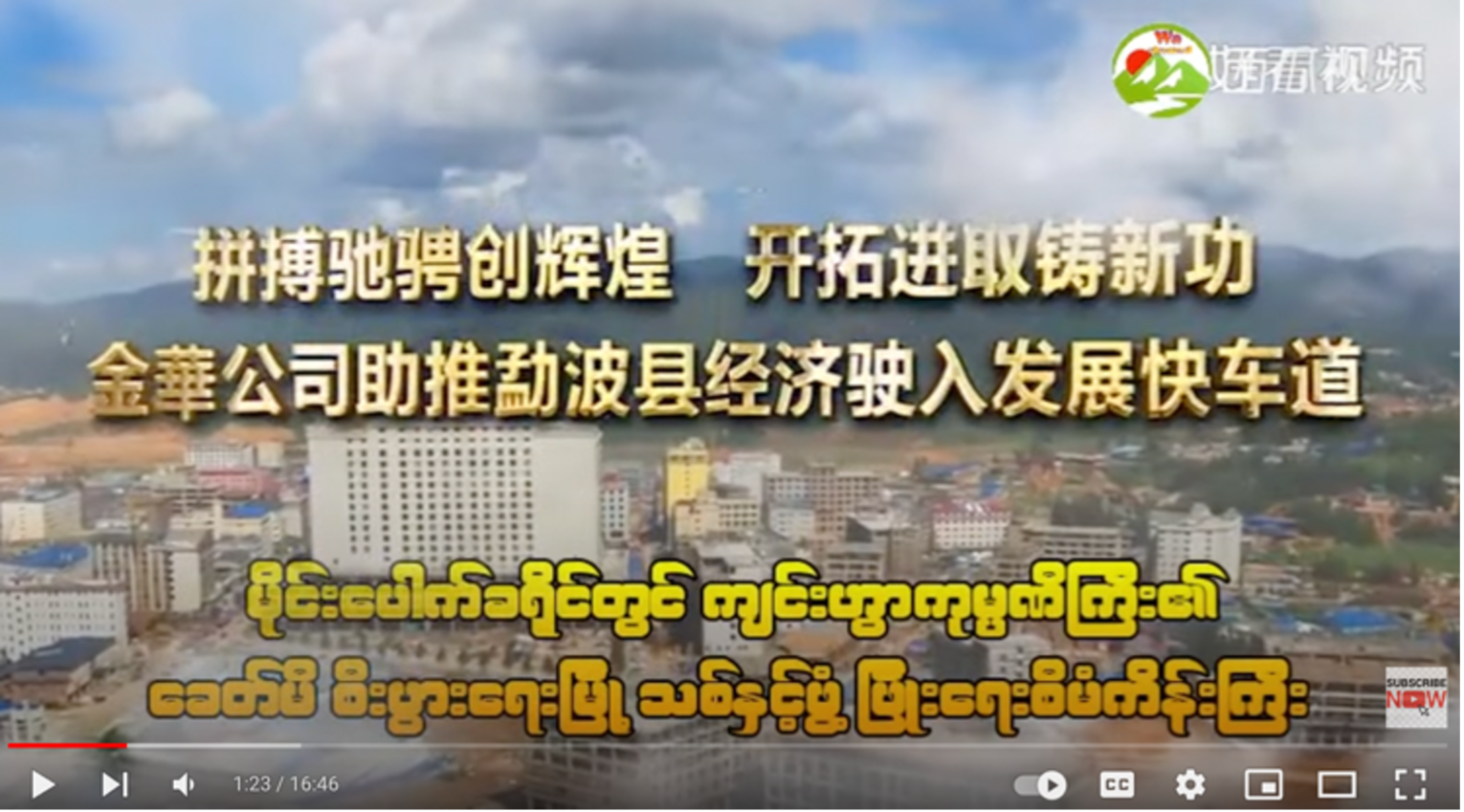

Mong Bawk was formerly a small agricultural trading village populated mainly by Lahu and Shan, about 25 kilometers southeast of Panghsang. Since 2015, with Chinese investment, the UWSA’s Jin Hua company has completely transformed Mong Bawk into a large town of modern, high-rise buildings.

A promotional video on the UWSA’s Wa Channel describes how the Mong Bawk Economic Development Zone was built on “vacant, fallow” land, but in fact farmlands and homes were seized from local villagers for construction of the new town.

The Kokang Self-Administered Zone

The young woman who was gang-raped by her Chinese boss and committed suicide was employed at an on-line casino in Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone.

Laukkai developed into a thriving casino town under the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) after its ceasefire in 1989. In 2009, a breakaway MNDAA faction joined with the Burma Army to oust the MNDAA and form a Border Guard Force. Today, the SAC regime and Kokang BGF jointly administer the Kokang SAZ.

TRAFFICKING PUSH PACTORS: EDUCATION DISRUPTION AND JOB LOSS AFTER THE 2021 COUP

The trafficking experiences in this report were a direct result of young people’s education or employment being cut short by the military coup on February 1st, 2021.

Three of the youth were students when the coup took place. “Jar Pan” (pseudonyms are used throughout this report) was a high school student who joined the anti-coup protests and refused to go back to study when the schools re-opened in June 2021. Under pressure from her parents to resume her studies, she resolved to find a job, which led to her being trafficked into the on-line porn industry in the Wa area.

Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw were university students at the time of the coup. Unwilling to study under military rule, they started work at a mobile phone company in Lashio, but the low pay led them to seek better job prospects in the Wa area. They then ended up being tricked into working as online scammers.

Nwe Nwe used to work as a nurse at a government hospital in Yangon. After the coup, she joined the civil disobedience movement (CDM) and participated in street protests against the junta. When violent crackdowns on protests began, she moved to stay with relatives in northern Shan State, but was hounded by the authorities and ended up fleeing to stay with a resistance group in the jungle. Unable to return to her former job, she sought work as a nurse in the Wa area, which led to her being trafficked into sexual slavery.

TRAFFICKING RECRUITMENT METHODS

Three of the youth were recruited through job advertisements posted on-line. Jar Pan responded to an ad on WeChat for Chinese-speaking hotel workers in Laukkai. Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw responded to ad on Facebook for males with basic English skills and computer proficiency to work with an on-line gaming company in Panghsang for a monthly salary of up to two million kyat.

Nwe Nwe was recruited by a former acquaintance working in Laukkai, who offered her a job as a nurse in Panghsang, where she could earn 2,000 yuan a month.

TRAVEL ROUTES TO TRAFFICKING DESTINATIONS

In the case of the three youth recruited on-line, they were asked to travel first to towns in northern Shan State, where they were met by agents, who then transported them by road — with other trafficking victims — to their respective destinations, all eventually in the Wa-controlled region.

Jar Pan was asked to travel to Kutkhai, where she and another friend looking for work were met by a man from Lashio called Ah Shan, who took them by car to Laukkai, where they were checked into a guest house together with three other women from northern Shan State. She had to undergo a Covid test, and then waited for three weeks without work, before being told that she would stand a better chance of finding a job in Panghsang, in the Wa region. She was then taken by Ah Shan with two other women in a car to Panghsang, where they stayed briefly before travelling to Mong Pawk. There the women had to undergo two weeks Covid quarantine in an apartment, before Ah Shan came to collect Jar Pan and hand her over to the Chinese criminals running the on-line porn business.

Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw were asked to travel first to Lashio, where they were met by a woman called Ma Nu. They waited there for four days before being joined by four other youth from Monywa, Magwe and Thayarwaddy. Together they travelled by mini-van via southern Shan State to Kengtung and then north to Mong Bawk, where they underwent one week’s Covid quarantine before being taken to their place of work.

Nwe Nwe, who was not recruited through an on-line ad, was asked to make her own way to Kengtung, where she was met by her acquaintance, who took her by car north to Panghsang in the Wa region. She was checked into a guest house, and then introduced to a Chinese man of Burmese origin, who offered her a job as a nurse for a Chinese company at a monthly salary of 2,500 yuan (about 350 USD) to which she agreed, little knowing that she would be held captive as a sex slave by on-line scammers. She later learned that her acquaintance had sold her to the male agent for 2,000 yuan, and the male agent had sold her to the scammers for 4,000 yuan.

TYPES OF EXPLOITATION AND ABUSE SUFFERED BY VICTIMS

Forced into online scamming

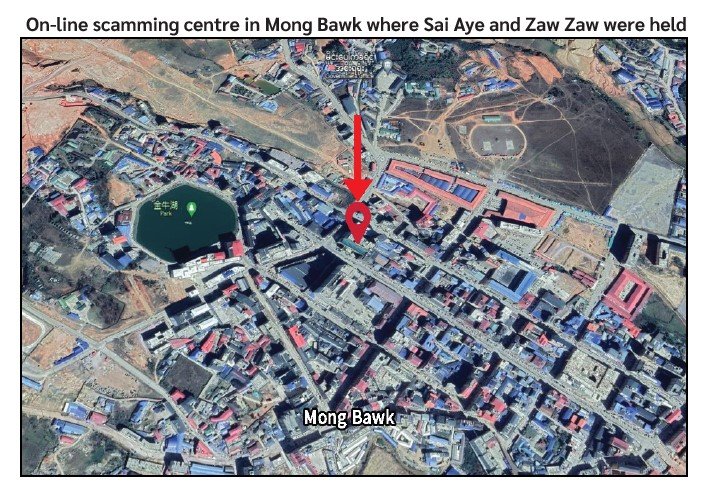

On arrival in Mong Pawk, Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw, the two university students, were tricked into signing a six-month contract with a Chinese company called Hua Long, believing it was an on-line gaming company. However, they soon realized that their job was to carry out cyber-scamming – referred to as “Kya Hpyan” in Burmese (from the Chinese word for scam – zhapian)

Their work involved using attractive images of Asian women to target individuals in Western countries, who they would engage in online communication and then persuade to invest in a fake cryptocurrency-accepting website. As soon as the money was invested, the fake website would be taken down. They were given a scamming target of three individuals a day.

The hours were from 8 am to midnight, Chinese Standard Time. They were closely monitored, and if they did not reach the scamming target their wages would be deducted accordingly.

The two youth did not want to carry out scamming, but decided to stay for one month, so that they could at least earn one month’s salary (3,000 yuan) before leaving. However, after three weeks, when they informed their employers of their decision to leave at the end of the month, they were no longer allowed to leave the work premises, and began facing physical punishment from the Chinese-speaking security guards if their targets were not achieved. For example, they were forced to run carrying a 5 litre bucket of water. After several days, when they insisted they wanted to leave, they were informed by the company manager that they would have to pay a sum of 12,000 yuan each if they left, and then locked up in a room, together with eight other employees who wanted to leave. They were allowed to phone their families to ask for money, but when they also posted about their situation on-line, appealing for help, they were handcuffed and beaten with rubber batons. Further torture included being forced to drink a two-liter bottle of water at one go, and being subjected to electric shocks from a stun gun.

Forced to take part in online pornography

Jar Pan, the high-school student who believed she would be working for an online casino, was sold to Chinese running an online porn business in Mong Pawk for the sum of 20,000 Chinese yuan. On realizing the nature of the work, she tried to refuse, but was told that if she didn’t want to work there, she would have to repay the sum of 30,000 yuan. She was locked up for three days, after which she was stripped down to her underwear by the security guards and slapped and tortured with electric stunners. She was then locked in a toilet without food for another five days, and tortured with electric shocks daily, until she agreed to start work.

For the first week, Jar Pan was forced to pose for nude photos, which she was told would be sold online. She was then told that she would be filmed having sex. When she resisted, she was caught and beaten by the security guards, who tied her up with rope and put her on a bed. She was then sexually assaulted by three men, who also beat and electrocuted her, all of which was recorded on film. When she returned to her room after this, she was shackled to her bed to stop her from escaping. A week later, she was raped again on camera, this time being beaten more brutally and having freezing water poured on her. This horrific ordeal continued for about two months.

Sexual slavery

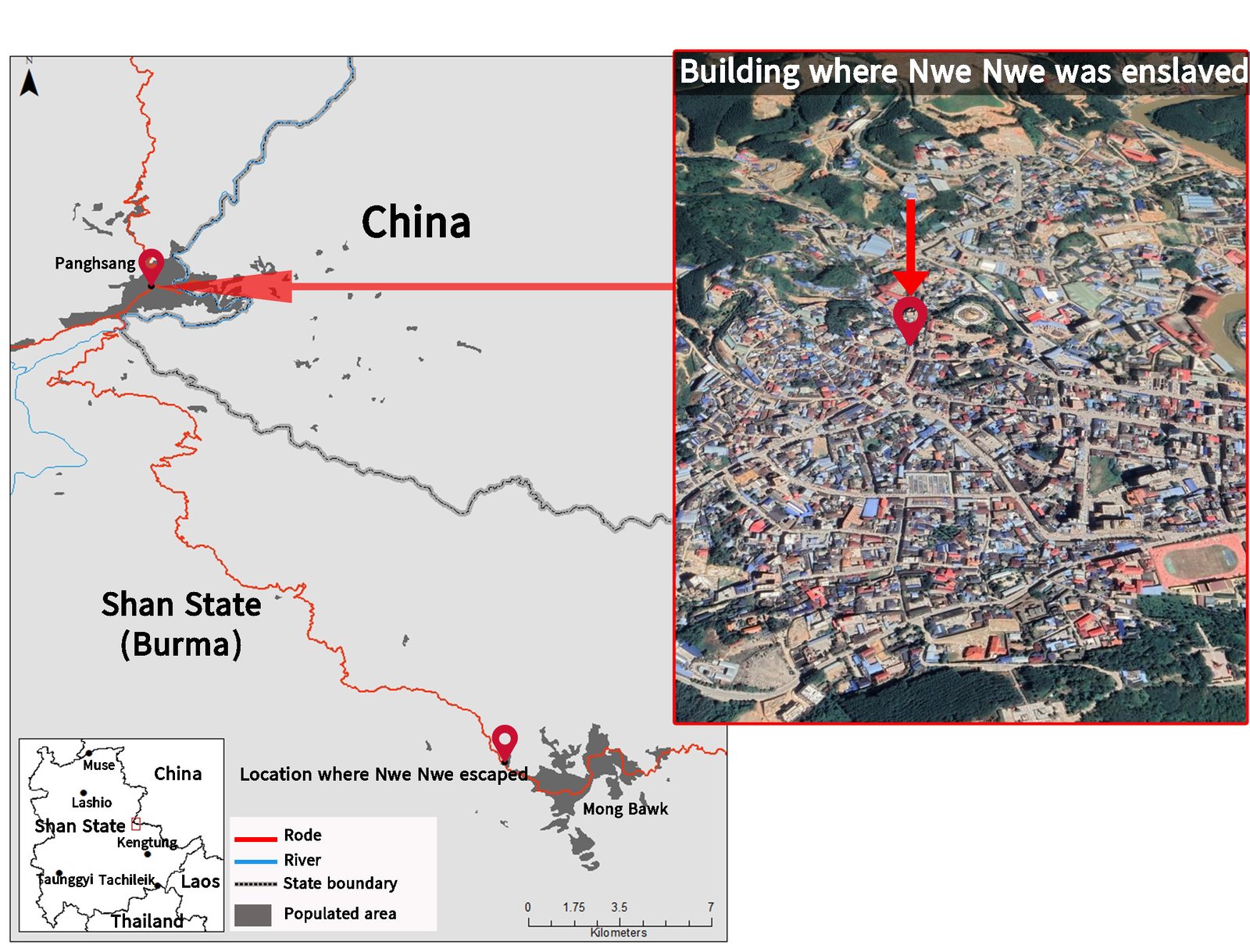

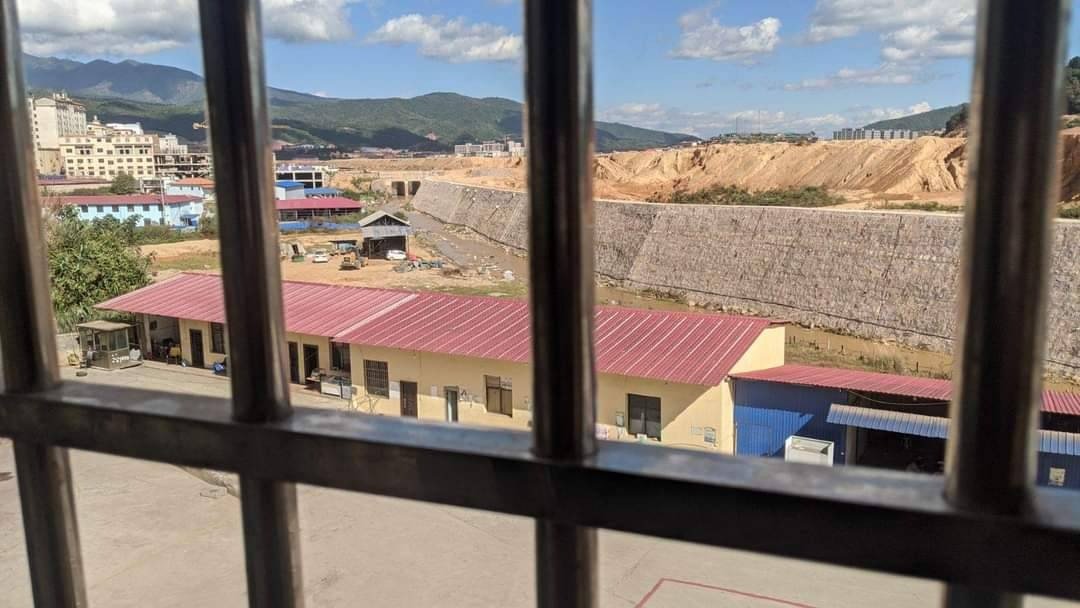

The CDM nurse Nwe Nwe, who believed she was being hired as a nurse, ended up being kept as a sex slave by Chinese running an on-line scamming business in the centre of Panghsang.

As soon as she was informed through an interpreter of the real nature of the work, she tried to leave, but was told she would have to pay 10,000 yuan to the company. She was then immediately sexually assaulted by the interpreter and another man. For the next two months, she was locked up and had to endure multiple sexual assaults every night. When she tried to escape, she was beaten with wires and belts by the Chinese-speaking security guards.

Gang-rape

A young woman called Nu Nu, who was hired as an accountant at the Ta Ying casino in Laukkai, was unjustly accused of embezzling 60,000 yuan. She was detained, together with her elder sister Sein Sein, who also worked at the casino, at a company building outside Laukkai where on-line scamming took place. Nu Nu was ordered to repay the money within one week. Five days after being detained, Nu Nu was summoned by her boss to a room in the Fully Light Hotel in Laukkai, where she was raped by the boss and three other Chinese men. Severely traumatized, Nu Nu committed suicide three days later by jumping from their room on the fourth floor.

METHODS OF RELEASE

Payment to captors

After being forced to take part in on-line porn videos for nearly two months, Jar Pan contacted her parents and asked them for help. She told them the company was demanding 30,000 yuan, and they must not seek help from the Burmese or Wa authorities or she would be transferred to a location far away inside China. It was then arranged for her parents to come and collect her in Mong Bawk. The company manager and three security guards brought Jar Pan to a pre-arranged restaurant in Mong Bawk, where she was handed over in exchange for the bargained down cash payment of 12,000 yuan. Her parents then took her home, without daring inform any authorities.

Contacting UWSA authorities

After Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw, together with seven other youth, had informed their bosses that they wanted to quit the online scamming company, they were confined in a room, and told they had to repay the sum of 12,000 yuan each if they wanted to leave. They were then permitted to phone their relatives to request this money. Fortunately, the parents of one of the women in their group had connections with a Shan militia group which helped them contact the UWSA’s liaison office in Lashio. This led to a raid by UWSA police on the building where the youth were being held, but at that time, the manager and all the other staff had already disappeared, with their equipment, having been tipped off in advance. The UWSA police took the youth into custody in Panghsang, and their parents were able to come and pick them up. The parents were brought to Panghsang with the Burmese police’s Anti-Trafficking Task Force, who escorted the youth back out of the Wa territory. However, each family had to pay 300,000 kyat to the Burmese police and 2,000 yuan to the UWSA police for the costs incurred during the rescue.

Physical escape

Nwe Nwe, the CDM nurse forced to be a sex slave for on-line scammers, was luckily able to escape while being transported by car with three other women (who had also been kept as sex slaves at the same building, but on different floors) from Panghsang to Mong Bawk.

After Nwe Nwe had contacted her family for help, her brother had got in touch with the UWSA liaison office in Lashio, and it appears that her captors had been tipped off, vacating all four women from their premises in Panghsang before a potential raid. They told the women that they intended to sell them into prostitution in Mong Bawk.

The women were being transported in two cars. When they stopped for a meal along the road to Mong Pawk, Nwe Nwe and another woman pretended to use the restroom and managed to slip away from the crowded restaurant. The other woman spoke Chinese and was able to contact a driver to pick them up and send them to Kengtung, where Nwe Nwe was reunited with her brother. Even though her parents wanted her to surrender to the military authorities and return home, she decided to cross the border to Thailand instead.

COMPLICITY OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES

The testimony of the interviewees suggests that the local authorities in both Wa and Kokang areas were allowing the criminal activities to take place, and even actively protecting the criminals.

Criminal enterprises located in town centres

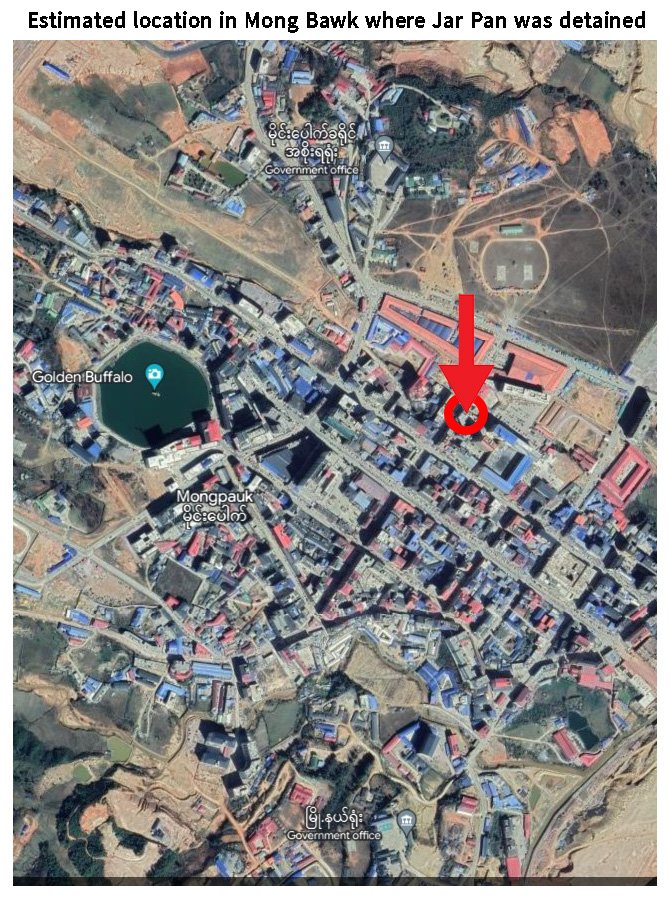

Maps show that the criminal enterprises to which victims were trafficked in the UWSA-controlled area were located in the town centres of Panghsang and Mong Bawk. The scamming tech support business where women were kept as sex-slaves was housed right in downtown Panghsang, close to the market, while the other criminal businesses in Mong Pawk were in large-multi-storeyed buildings in the central town district.

These enterprises were all being run by Chinese nationals, who could not have entered the UWSA territory and set up businesses there without official permission (and financial contracts). It is therefore highly unlikely that they would have dared carry out their criminal operations, involving systematic torture and abuse of workers (that any neighbours would have been well aware of), on their rented premises in town centres if there was not tacit official approval for them to do so.

Criminals tipped off in advance

In both cases where family members contacted the UWSA liaison office in Lashio for help, the Chinese criminals were tipped off before any action could be taken against them. In the case of Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw, the entire staff of Chinese scammers moved out (with their equipment) the day before the UWSA police “raided” the building and rescued the ten youth locked up there.

In the case of Nwe Nwe, the Chinese scamming-support criminals who were using her and three other girls as sex slaves transferred them out of their workplace in Panghsang to Mong Bawk, which would have made it impossible for her to be traced if she had not escaped.

Local militia guarding criminal premises

Sein Sein, whose sister Nu Nu was gang-raped by her employer in Laukkai, recounted that their company’s on-line scamming centre where they were detained (and where Nu Nu committed suicide) was heavily guarded by uniformed members of the Kokang Militia Force (KMF). These militia witnessed Nu Nu commit suicide, and were present when company staff came to collect and dispose of her body, after which the staff threatened Sein Sein at gunpoint not to reveal what had happened.

The KMF is a locally recruited force set up and armed by the Burma Army to help maintain control of the Kokang SAZ. This indicates high level complicity in the criminal operations which the KMF are openly guarding.

USE OF MYTEL FOR ON-LINE SCAMMING

The interviewees forced to carry out on-line scamming in Mong Pawk said they used the Mytel network, the only Burmese telecom network available in the UWSA area of northeast Shan State. Previously, residents of Panghsang and Mong Pawk had relied on Chinese telecom networks, but since Mytel extended its network to this area four years ago, most people have switched to Mytel, the joint venture between Vietnam’s state-owned Viettel and the Myanmar Economic Corporation, the Burma Army’s business conglomerate.

Given the SAC regime’s direct control of Mytel, and their extensive surveillance capability, this begs the question why they are taking no apparent measures to crack down on the widespread use of their own network for cyber crime in the Wa area.

TESTIMONIES OF INDIVIDUAL SURVIVORS

Jar Pan

Jar Pan is a 19-year-old Kachin woman from Namkham in Northern Shan State. In 2021, the year the military staged the coup, Jar Pan was still attending high school. However, when the schools were instructed to reopen in June 2021 by the State Administration Council (SAC) regime, Jar Pan chose to participate in the civil disobedience movement and refused to return to school.

Despite her involvement in the anti-coup movement, Jar Pan’s family insisted that she resume her education. To escape the constant pressure and arguments with her family, Jar Pan resolved to leave home and find a job.

In June 2022, Jar Pan came across a job advertisement on social media, which inspired her to get in touch and apply.

“I was actively searching for employment opportunities during that time. My primary intention was to leave my home because my family insisted that I take the matriculation exam the following year. They wanted me to attend online tuition and preparation classes, but I had no interest in taking the exam. Therefore, I made the decision to leave home and started looking for jobs. I came across a job opening on WeChat, which required applicants to be based in Laukkai and have knowledge of Chinese. I contacted a man named Ah Shan from Lashio, who informed me to wait for a while as he was still gathering a few applicants. The job involved working at hotels, and the business owners would cover the travel expenses for us. He instructed me to come to the designated location,” Jar Pan explained.

Ah Shan, the contact person, got in touch with Jar Pan in August 2022 and advised her to receive a Covid vaccination provided by the government. Following that, she received instructions to meet at the Aung Chan Tha restaurant in Kutkhai at 2 pm on August 27, 2022.

On August 27, 2022, Jar Pan and her friend Lu Lu, who also sought employment, informed their parents that they would be traveling to Lashio for a short period. They left their home and took a taxi to Kutkhai. Later that day, they departed from Kutkhai to Laukkai in the evening

They finally reached Laukkai on the same day, at around 8 pm. They were placed at Shin Ba Li guest house together with three other women from Lashio, Tangyan and Nam Zalap towns.

“On the night of the 27th, we arrived in Laukkai. Ko Ah Shan arranged for us to stay at a guest house along with others who had come from Lashio and different places. In total, there were eight of us. On our first day there, Ko Ah Shan provided us with instant noodles and snacks. He informed us that we would need to undergo a Covid-19 test the following morning. We were taken to a clinic in Tone Cheng, a suburb of Laukkai, for the test. Afterwards, Ko Ah Shan explained that due to the Covid-19 outbreak, job opportunities in Laukkai were limited. However, there were plenty of job opportunities in the Wa region. He asked if I wanted to go there. With my Chinese language skills and educational background, I agreed to go, expecting to secure a position at a casino. However, my friend Lu Lu, who accompanied me, had limited Chinese language proficiency and decided to stay in Laukkai and explore the available job opportunities,” Jar Pan recounted.

In late September 2022, after spending three weeks in Laukkai, Jar Pan embarked on a journey to Mong Bawk with two young women from Lashio and their broker, Ah Shan. Despite the lockdown imposed by the UWSA on the entire Wa Self-Administered Region, including Panghsang, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, they managed to enter the region by following a route planned by Ah Shan.

Following a brief stay in Panghsang, Jar Pan arrived in Mong Pawk on September 30, 2022. She underwent a 14-day quarantine period in an apartment near a temple in the town. On October 15, the broker Ah Shan arrived to collect only Jar Pan. He took her to an unmarked building near Mong Pawk market, where she was introduced to a male manager and female assistant manager who she would be working under. Both were Chinese nationals.

On that day, Jar Pan’s nightmare began. The establishment she had been brought to was involved in the production and distribution of online pornography. Ah Shan had sold her to the business for the sum of 20,000 Chinese yuan.

“After Ah Shan left, the assistant manager led me to the room where I was to stay for the night. She said she would discuss the nature of my work the following day. I shared the room with a girl from China, who asked if we would be engaged in chatting or modeling. Assuming I would be working at an online casino, I replied that I would be chatting. I had no idea what kind of industry I had been sold into. The next morning, the female assistant manager and two other men came to take me to an office room and informed me, ‘You are beautiful and young, so you should become a model.’ Confused, I asked them what kind of model. They showed me photos of naked girls, some of whom were tied up with ropes. They told me I would have to take similar pictures and videos. I said I didn’t want to and expressed my desire to return home. They informed me that I had been sold, and if I wanted to go back, I would need to pay 30,000 yuan. I pleaded with them, requesting to contact my friends and family. They granted me three days to consider but locked me in an empty room, providing only one meal in the morning, consisting of rice with pickled mustard leaves,” said Jar Pan.

During the three days locked in the room, Jar Pan tried to contact both the broker Ah Shan and her friend Lu Lu, who had chosen to remain in Laukkai. However, she was unable to reach them. Jar Pan was reluctant to reach out to her family and inform them about her predicament, as she felt responsible for leaving home in the first place.

“During those three days, they didn’t confiscate my phone. I attempted to contact the broker Ah Shan, but he had blocked me on WeChat. I also reached out to Lu Lu, my friend who had accompanied me, but received no response. I felt deep shame for having been sold into such a situation, so was hesitant to approach other friends for help. I knew that my decision to leave home was my own, and was aware that my father did not have the means to pay for my release. Fearful of burdening my family further, I refrained from reaching out to them. I spent those three days of confinement racking my brains about what to do,” said Jar Pan.

Three days after being confined, the manager, the assistant manager, and three security guards (ethnic Wa, who spoke Chinese) approached Jar Pan in her room, demanding her decision. She explained she was unable to provide the compensation money but did not want to engage in the work offered. The manager insisted she had to work, as they had already invested money in her. They threatened to report her to the local police for fraud if she refused. Prior to involving the police, the manager warned that he would teach her a lesson and ordered the security guards to forcibly remove her clothes.

“The security guards forcefully stripped me of my clothes and confiscated my phone. There were too many of them for me to resist. I was left with only my underwear. The manager proceeded to slap me, while the two security guards tortured me with electric stunners, all over my body. Following the ordeal, the female assistant warned me that if I didn’t want further harm, I had to comply with their demands. They said that once I repaid the expenses they had incurred, they would release me. Filled with fear, I was unable to voice any objections. They then confined me in a small toilet for the next five days, depriving me of meals. When they brought me drinking water in the morning, they inflicted further electric shocks. After five days, my body was barely responsive. Helpless, cold, and hungry, I finally succumbed to their coercion and agreed to work for them,” recounted Jar Pan.

The following day, the female assistant escorted Jar Pan to a room where two women applied make-up on her. Once ready, she was led to a building containing a photo studio room. There, she was forced to pose for nude and sexually explicit photographs, under the direction of the individuals working there.

When Jar Pan requested the return of her mobile phone, the female assistant informed her that it would be returned after monitoring her situation for two weeks. She shared a room with two women from the Irrawaddy Region. They had previously worked as singers at beer bars and restaurants and had willingly joined the industry through their own connections. Despite complying with the demands to pose naked, Jar Pan soon experienced even worse abuse.

“I was forced to pose for various types of pictures every other day. Some involved being tied up with ropes, while others required posing with another girl. I had to follow their instructions. They mentioned that these pictures would be posted and sold online, although I don’t know on which website. After a week of taking pictures, they asked me to put on clothes that were not my usual attire. When I entered the room they directed me to, there were three unfamiliar men present. This time, they wanted to film a video of me sleeping with those men. I desperately tried to escape, but the security guards caught and beat me, tying me up with ropes and forcing me to get on the bed. The three men in that room then subjected me to further beatings, electric shocks, and sexual assault. All of this was recorded on camera,” said Jar Pan.

When she returned to her room after this abuse, her feet were shackled to prevent her from fleeing. About a week later, they raped her once more on camera. The second time, they beat her more brutally, and poured freezing water on her. This pattern of abuse continued for about two months until finally, Jar Pan mustered the courage to request her phone back from the male manager. She expressed her intention to contact her family and arrange for the necessary money for her release.

When Jar Pan contacted her family, she explained the situation to her father and pleaded for financial assistance to secure her release. However, the company warned that after paying 30,000 yuan, Jar Pan’s family should on no account notify or seek help from the Burmese or Wa authorities. Failure to comply would result in Jar Pan being transferred to a location far away inside China.

On December 24, 2022, Jar Pan’s father and mother met with the male manager and three security guards in Mong Pawk. The meeting took place at a restaurant where Jar Pan was handed over in exchange for a cash payment of Myanmar kyat equivalent to 12,000 Chinese yuan.

On December 26, 2022, Jar Pan finally arrived back in Namkham. Months after her release, she continues to suffer from the trauma of her horrendous experience.

Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw

Sai Aye, a 21-year-old from Hsipaw, and Zaw Zaw, a 19-year-old from Kyaukme, first met while working as sales staff in a mobile phone company in Lashio. Sai Aye had been a third-year student studying mathematics at Lashio University, while Zaw Zaw had been a first-year student at Technology University (Mandalay). Their education had been halted due to the military coup, and they did not want to continue studying under the military regime.

Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw started working for the phone company in June 2022, receiving a low monthly salary of around 150,000 Myanmar kyat. Together with commission fees, they could only earn up to 180,000 kyat per month. This income was barely enough to cover their basic needs, including food, motorcycle fuel, and a monthly rent of 40,000 kyat. They could barely support themselves, let alone provide for their families. As a result, they started to look for other options for a better job and income.

One day, Sai Aye came across a job advertisement on a Facebook group and shared it with Zaw Zaw. The announcement was for a position related to online gaming in Panghsang, in the Wa region. The ad specified that they were seeking male employees with basic English skills and computer proficiency, offering a salary of up to two million Myanmar kyat per month. Intrigued by the opportunity, both Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw expressed their immediate interest in the job and contacted the provided Viber number.

On October 8, 2022, Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw met with a woman called Ma Nu in Lashio. She claimed to be an agent for a boss from Panghsang, and informed them that they were hired. They were told to wait for four more people from Monywa and Magway before traveling to the Wa region via Kengtung on 12 October.

On October 12, Sai Aye, Zaw Zaw, and four others from Monywa, Magway, and Thayarwaddy left Lashio for Kengtung in a minivan, making a total of six passengers. They travelled via Laikha, Kho Lam and Mong Paeng, arriving in Kengtung on October 13, and the following day, on October 14, they reached Mong Pawk in the Wa region.

As Sai Aye, Zaw Zaw, and the others had initially been told they would be working in Panghsang, they asked Ma Nu why they had been taken to Mong Pawk. She explained that even though the company’s main office was in Panghsang, they had a branch in Mong Pawk. After that, Ma Nu left them at a hotel to undergo Covid quarantine.

A week later, Ma Nu returned to take Sai Aye, Zaw Zaw, and the others to a company named Hua Long, which occupied a six-floor building in Mong Pawk. Upon arrival, they were asked to sign a six-month contract with a monthly salary of 3,000 yuan (about 420 USD). They were informed that they would have a one-week trial period, and if they were not satisfied with the job, they would be allowed to leave. Ma Nu introduced them to their Chinese translator, Lin Wai (from Burma), and then left.

Zaw Zaw explained that he had no idea beforehand that the job would involve online scamming, commonly referred to as Kya-hpyan, from the Chinese term “ziapian”.

“The job they initially promised us was completely different from the work we were forced to undertake. Instead of being involved in the online gaming industry, we were assigned to work on fraudulent activities and scams known as Kya-hpyan. Our role was to use attractive images of Asian women to specifically target individuals from Western countries. We had to engage in online communication, including engaging in explicit conversations. The next step was to persuade them to invest in a cryptocurrency-accepting website that was entirely fabricated. As soon as the money was transferred, the fake website would be taken down,” said Zaw Zaw.

“We were given a target to scam at least three individuals per day,” explained Sai Aye.

Sai Aye felt bad about scamming innocent people, but endured the job because he felt he had little other alternative and thought he could quit after one month and still get paid. They had to work from 8 am to midnight, China Standard Time. Their working hours were closely monitored, and any days they couldn’t reach the required targets would result in deductions from their salaries. They were working on the second floor of the building, where 12 other youth, including three women, were involved in scamming. The company employed over 40 scammers on the different floors, overseen by about ten Chinese staff.

According to Sai Aye, after they informed the boss of their intention to leave the company a week before completing the first month, they noticed a change in the way they were treated by the company.

“After the six of us, along with the three girls who were already there, expressed our intention to quit one week before the end of the month (November), we noticed a change in the way the company treated us. Previously, during break time, we were allowed to go out and buy snacks. However, after we informed the company about quitting, we were told by the security staff not to leave the premises due to Covid-19 restrictions. Previously, there was only salary deduction for failing to meet scamming targets, but after notifying the company about their decision to quit, they began facing physical punishment if the targets were not achieved. The women were subjected to kneeling for hours, while the men were required to run while carrying a 5-liter bucket of drinking water,” said Sai Aye.

The punishment was carried out by the company’s Chinese-speaking security guards, who wore black uniforms. After enduring this abuse for several days, on November 28, the nine victims once again conveyed their decision to quit the company. In response, the manager of the company revealed that they had been sold for 6,000 yuan each, and in order to leave, they would each have to repay the company a total of 12,000 yuan. Following this revelation, the manager locked ten of them in a room (including another youth, who said he wanted to leave after seeing how the others were tortured), and confiscated their phones.

After they had appealed to the manager and explained they needed to contact their families to arrange the necessary funds, the phone of one of the women was returned. With access to a mobile phone, each of them contacted their family to let them know about their situation. In addition, they posted about their situation online and asked for help.

The next day, the company manager and about ten security guards arrived with rubber batons, handcuffed them and beat them for about 20 minutes, because they had posted the story online. Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw were incensed to see one of the security guards slapping a woman who resisted the beating, and began punching the security guards.

This led Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw to suffer even more severe retaliation. They were subjected to further beatings and then confined in a cell on the sixth floor of the building.

“They separated the two of us from our group and took us to the top floor and locked us up. The room was completely dark. Six of them beat me up with rubber batons. When Zaw Zaw fought back against them, they dragged him to the toilet. They took off his shirt and beat him. Then they turned on the toilet water hose and inserted it into his anus. They handcuffed me to a bed, and handcuffed Zaw Zaw behind his back and left him in the toilet,” recounted Sai Aye.

In the subsequent days, Sai Aye and Zaw Zaw were given only one meal per day. They were repeatedly asked to return the money they owed. They also suffered further abuse, including being forced to drink a two-liter bottle of water in one sitting, being subjected to electric shocks from a stun gun, and being beaten with batons. This continued for a week after being separated from the rest of the group. Meanwhile, the parents of one of the women in their group had reached out through connections with a local Shan militia group to the UWSA’s liaison office in Lashio to report the case.

On the morning of December 24, the UWSA police conducted a raid in the area where the victims were being held captive. However, by that time the manager and other staff members had already fled, taking all their equipment, having been tipped off about the raid. The ten individuals who had been detained were taken into custody by the UWSA police and subsequently handed over to their parents who had come to pick them up in Panghsang, together with the Burmese police’s Anti-Trafficking Task Force.

Zaw Zaw described their release, “We were released from the building on December 24th. On the 25th, my father came to pick us up. I had contacted him before being detained. The other members of our group had also reached out to their families for help, and fortunately, one of them had connections with a local Shan militia group, who assisted in arranging our release. Each of us had to make a payment of 300,000 Myanmar kyat to the Burmese police and 2,000 yuan to the Wa side to secure our release.”

Upon returning to home, Zaw Zaw had to undergo a week of medical treatment at a private clinic in Kyaukme town to treat the injuries he had suffered during his ordeal.

Nwe Nwe

“I escaped from the horrors of the dictatorship, only to find myself trapped in another nightmare.” Nwe Nwe, a 29-year-old resident of Yangon Before the military coup in 2021, Nwe Nwe worked as a nurse at one of the government hospitals in the Yangon Region. When the military seized power, she actively participated in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) against the regime.

During the entire month of February 2021, Nwe Nwe joined in peaceful protests against the military dictatorship. However, following violent shootings and crackdowns on peaceful protesters in Yangon, her family started to worry for her safety. They asked Nwe Nwe to go and stay with her grandmother in Nawng Khio, in Northern Shan State.

Upon reaching Nawng Khio, Nwe Nwe continued her involvement in the resistance movement. She actively engaged in efforts to raise funds and provide support to local civil servants who were participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). She also helped young individuals joining the emerging armed revolution.

In May 2021, military council troops and police came searching for her at her grandmother’s home. Fortunately, she was notified prior to the raid and managed to escape to an area controlled by an ethnic armed group.

“From May to October 2021, for the first six months, I stayed in an area controlled by one of the ethnic armed organizations. Then, when the situation in that area became unstable, I relocated to Ho Pong (in southern Shan State) to stay with one of my friends,” said Nwe Nwe.

The longer Nwe Nwe was on the run, the more difficult it became for her to support herself. Initially, her family and boyfriend were able to support her, but when her boyfriend joined the armed resistance in January 2022, it became necessary for Nwe Nwe to find work.

In September 2022, Nwe Nwe got in touch with an acquaintance called Nang Lao, who was working in Laukkai. Nang Lao told her she could find her a job as a nurse in Panghsang, in the Wa region, where she could earn a monthly salary of 2,000 Chinese yuan. She mentioned the high demand for nurses in the area and offered to connect her with relevant job opportunities if she was interested.

After careful consideration, Nwe Nwe decided to go and meet Nang Lao and explore job opportunities. Following Nang Lao’s instructions, on October 9th, 2022, Nwe Nwe traveled to Kengtung by road via Namzarng, Kho Lam and Mong Paeng, and Nang Lao met her there as planned. Together, they travelled by car to Panghsang.

In the final week of October 2022, Nwe Nwe and Nang Lao reached Panghsang and checked into a guest house. It was there that Nang Lao introduced Nwe Nwe to Tin Aye, a Burmese national of Chinese origin. Tin Aye informed Nwe Nwe she would be working as a nurse for Chinese nationals employed in the companies in Panghsang. She would receive a monthly salary of 2,500 yuan, and an interpreter would also be available to assist her with communication.

Having agreed to the job offer, Nwe Nwe was escorted to a four-storey building near the Panghsang market on November 3rd. Tin Aye introduced her to another Burmese national of Chinese origin named Ah Wei, who was working as an interpreter for the company, and then left her.

Ah Wei made arrangements for Nwe Nwe to stay in one of the rooms in the building. Nwe Nwe was not aware at the time that Nang Lao had sold her to Tin Aye for 2,000 yuan, and that Tin Aye had then sold her to the company manager for 4,000 yuan.

She soon discovered that she had been brought to provide sexual services to Chinese men working at the company, which provided technical support services for online scamming companies in Panghsang. She was informed of this by the interpreter Ah Wei, who entered her room with another Chinese man.

Ah Wei told her that she needed to pay 10,000 yuan as compensation if she wished to return home, and since she had already been brought to the company, she would have to comply with their demands. Ah Wei and the other man then sexually assaulted her.

“As there were two of them, I wasn’t able to defend myself. I tried to resist by throwing objects within reach and using any means available to me. But my efforts were in vain. From that night on, every night became an unbearable nightmare. The room was locked from the outside, leaving me trapped. They provided me with meals twice a day, but the nights were filled with repeated sexual assaults, carried out by two or even four men,” Nwe Nwe recounted.

After she had been enduring this abuse for a week, Nwe Nwe tried to escape. When the person delivering her rice arrived, she summoned the strength to push him aside and made a desperate dash downstairs. However, her escape attempt was short-lived because she was caught by the Chinese-speaking security guards on duty at the premises. She was forcefully taken back to the room, where she was beaten with wires and belts.

After this unsuccessful escape attempt, Nwe Nwe persistently pleaded with the interpreter Ah Wei to return her phone so she could contact her family. She eventually got her phone back on December 19th, 2022, and called her family right away.

She told her oldest brother about her situation, and he immediately took action by posting about it online and looking for help. Then he went to Lashio town with a friend to ask the UWSA liaison office for assistance. A liaison officer assured him they would help with the situation, but asked him to wait for a while.

While Nwe Nwe’s brother was finding a way to rescue her, the company that had detained her was making plans to traffic her to another location with the three other young women enslaved in the same building. On January 2, 2023, Nwe Nwe and the three other women were informed they would be taken to Mong Pawk, where they would be sold into prostitution.

“They held a knife and forced us into cars. They had discovered that information about us had been leaked, so they decided to transport us to Mong Pawk. I made another attempt to escape, before getting into the car. Because of that they slashed my breast with the knife. We were transported to Mong Pawk in two separate vehicles. In my car was another young woman from Nam Hsan who, like me, could speak Shan. We talked to each other about the possibility of escaping,” Nwe Nwe recounted.

When the cars stopped at a restaurant for a meal along the road to Mong Pawk, Nwe Nwe and the other woman saw an opportunity for escape. Telling their captors they had to use the bathroom, they managed to slip away out of sight. Their captors, who numbered only three people, were unable to chase after them in the crowded area.

“The companion who escaped with me was able to speak Chinese fluently. She had been trafficked due to an unpaid debt to her boss. She had some Chinese currency with her and also had some connections. Once we managed to escape from the vehicles, we sought refuge in a nearby restaurant. She contacted one of the drivers she knew and arranged for him to pick us up. Meanwhile, I contacted my older brother and updated him on the situation,” said Nwe Nwe.

At 2 pm on that day, they departed from Mong Pawk, and by 7 pm, they reached Kengtung. They found accommodation at a guest house in Kengtung, where they spent the night. The following day, Nwe Nwe’s brother arrived by plane to meet her. Her family encouraged her to sign a pledge to the military regime that she would not be involved in political activities and return home, but Nwe Nwe chose a different path. She decided to illegally cross the border into Thailand with the assistance of a friend in Tachileik.

“In the last week of January, my brother and I crossed over to Thailand. My brother rented a house for me in Mae Sai, and then he went back. Although I am free, I feel a deep sadness when I think about the other two girls who were left behind. We barely managed to escape ourselves. While I am now physically free, mentally I am still suffering and have trauma from those experiences. I know I need counseling services to help me heal. But I am not disheartened, and I will not give up. I will continue to do everything I can to prevent more women from falling into the same situation I experienced. I will also continue to resist the military dictatorship that pushed us into such a situation,” Nwe Nwe explained.

With the support of friends, Nwe Nwe has found employment caring for the elderly in a city in Thailand. She is currently undergoing counselling to heal from the mental trauma she has endured.

Sein Sein

Sein Sein never dreamed that the well-paying job she enjoyed and believed would provide for her family would ultimately claim the life of her beloved sister, Nu Nu.

Sein Sein and Nu Nu had Chinese parents, born in Burma. In 2019, when Sein Sein turned 18 years old and completed her high school education at a Chinese school in Burma, she was introduced to a job opportunity by one of her friends. This led her to Laukkai, where she started working at a casino establishment known as Ta Ying.

Sein Sein explained that she had started working as a card-dealer (or “fei show”), for gamblers at the casino. Eventually, by the end of 2020, she was promoted to the position of cashier. It was during this time that she decided to bring her younger sister, Nu Nu, to work with her.

“In December 2020, I went back home to bring my younger sister with me. The salary offered for the position was around two million Myanmar kyat per month, and our parents were supportive of her coming along, especially since we have relatives in Laukkai,” Sein Sein recalled.

Nu Nu, who had training in accounting, was given a job in the accounting department of the casino. The two sisters stayed at a dormitory provided by the company. Throughout 2021, both sisters continued working at the casino without any disruptions, despite the political upheaval in Burma and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Due to travel restrictions imposed between China and Burma, the casino company had shifted its operations to online platforms. Sein Sein was given the job of translating short Chinese video clips into Burmese and sharing them on social media platforms with advertisements promoting the company’s gambling business.

In the first week of November 2021, Sein Sein and Nu Nu’s lives took a drastic turn. Shan Ti, the Chinese national in charge of the business, called upon Nu Nu in the evening of November 5th and accused her of stealing 60,000 yuan from the business account.

Nu Nu fiercely refuted the charge, arguing that she wasn’t the only one with access to the account and that others were also responsible for managing it. However, the manager and the accounting division took the boss’s side and accused Nu Nu of stealing. They threatened to turn her over to the local Kokang militia if she didn’t pay back the 60,000 yuan stolen. No evidence was shown to back up the accusation.

“We can never know for certain if there was really a discrepancy in the money account, or if it was fabricated by the company. It is highly unlikely that my sister would have stolen the money. All the transactions were conducted online and through Chinese bank accounts. However, none of the managers or heads of the accounting department supported her. Instead, they accused her of theft and demanded repayment,” Sein Sein explained.

That evening, to prevent them escaping, Sein Sein and Nu Nu were forcefully taken from their dormitory and transported to a five-storey company building located about 8 kilometers northeast of Laukkai town, close to the main border crossing into Nansan, China. The building was heavily guarded by armed men in Kokang militia uniforms, and was being operated as an on-line scamming centre.

The company demanded that Nu Nu repay the money within a week and confined both sisters to the same room. On the fifth day, the boss made a phone call to Nu Nu and instructed her to accompany another individual to the Fully Light Hotel in Laukkai town. Nu Nu complied and left in seemingly good condition, but upon her return, she was visibly injured and in tears.

“That day, when my sister returned, she was covered in injuries and couldn’t stop crying. She revealed that the boss, along with three other Chinese men, had sexually assaulted her in a hotel room. They also threatened to sell her into a brothel in the Wa region if she failed to repay the money. The injuries she sustained were a result of her bravely trying to resist their sexual abuse,” Sein Sein recounted.

Sein Sein then frantically began contacting her family and uncle for support. Her uncle cautioned her, however, that filing a complaint with the local authorities would be difficult because the area was governed by the Kokang BGF. Her parents and family members from Lashio appealed directly to the company, proposing to sell the family house in Lashio and pay half of the sum needed to free the sister.

Nu Nu was devastated by the sexual assault she had suffered. She cried every day and refused to eat. She kept telling Sein Sein not to burden their family with her troubles, and Sein Sein complied, never imagining the terrible course of action her sister would take.

On the eight day of their detention, Sein Sein was startled by a loud banging sound from the window while she was in the bathroom. To her horror, she discovered that Nu Nu had jumped from their room, which was on the fourth floor. Sein Sein shouted for assistance, begging the security guards to open the door. She hurried downstairs, but Nu Nu had already passed away after colliding with the concrete road and suffering a fatal head injury.

Later that night, people from the company arrived to take away Nu Nu’s body and cremate her right away. Sein Sein was threatened by armed men not to disclose the news of the suicide to anyone.

“I was almost losing my sanity. My sister’s life had been taken away because of the boss I had been working with for a long time, and I couldn’t even retrieve her remains. They warned me not to share a word about the incident to anyone, and demanded that I return home immediately. They even threatened to arrest my uncle who resided in Laukkai town. The following day, I had no choice but to pack my belongings and return home,” Sein Sein recounted.

After Sein Sein returned to Lashio and told her partners the terrible story, her father’s health deteriorated, and he became bed-ridden. She badly wanted to report the incident to the police and seek justice, but realized she did not have enough evidence and her family did not have enough money to pursue the case. The ongoing political unrest also discouraged her from taking action, as did her knowledge of collusion between the Kokang authorities and her former employer.

“I am concerned for my uncle who remains in Laukkai. My father is also unwell. Since I did not have evidence, I could not do anything. Even if I share it with people, they will think that I am lying. So I couldn’t do anything and dared not share this incident with anyone,” said Sein Sein.

Sein Sein has now decided to share her story, because she says that she does not want other young people to endure what her sister did, and wants to warn young people about the risks associated with pursuing jobs along the border.

Conclusion

The harrowing testimonies in this report give just a small glimpse into the widespread abuse being inflicted on countless victims from Burma and other countries enslaved by criminal gangs in the Kokang and Wa areas of northeast Shan State.

We hope that by sharing these experiences we can warn other youth in Burma of the risks of migrating to work in these areas, so they can protect themselves from being similarly trafficked and abused.

It is also urgently needed for the relevant authorities to crack down on the criminal gangs operating in their territories and to hold them to account for the abuse inflicted on their enslaved victims.

SHRF therefore makes the following calls:

- We urge the authorities in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone and the UWSA-controlled area of northeast Shan State to stop colluding with and protecting the Chinese criminal gangs operating in their territories.

- We urge the government of China to take more effective measures to hold their citizens to account for involvement in criminal activities in the Kokang and Wa regions of Shan State.

- We urge the government of Vietnam, whose state-owned Viettel is a joint partner in Mytel, to investigate the use of Mytel network for cyber crime in northeast Shan State.